The SdKfz 251 stands with the Panzer IV at the focal point

of Wehrmacht armor. Its only rival for “best of its kind” was its US army

counterpart. It was a bit of a military afterthought. German infantry had

regularly ridden trucks to the combat zone during maneuvers since the

Reichswehr years. In the early days of the armored force, motorcycles were so

popular that five of the nine rifle companies in a panzer division’s rifle

brigade rode them. Trucks and cycles, however, shared common problems: high

vulnerability and limited off-road capacity. On the other hand, the panzers’

commitment to the principle of close tank-infantry cooperation was reinforced

by the experiences of both sides in the Spanish Civil War, when tanks operating

alone in broken or built-up terrain proved highly vulnerable to infantry who

kept their heads. In a 1937 exercise, the modified civilian two-wheel-drive

trucks assigned to the motorized infantry performed so badly that Guderian,

still a mere colonel, directly challenged the armís commander in chief, Werner

von Fritsch, to remedy the situation.

“Had my advice been followed, we would now have a real

armored force” were bold words, often cited to prove Guderian’s professional

conviction, his moral courage, and his arrogance, depending on the author’s

perspective. In fact, exercises and maneuvers were historically regarded as high-stress

situations where such outbursts were more or less predictable, and Fritsch had

a known high tolerance for young enthusiasts. Guderian, moreover, was widely

understood as Lutz’s protégé (an alternate German word is Protektionskind,

“favorite child”). In short, he got away with it.

In concrete terms, Lutz and Guderian pressed for the

development of an infantry-carrying vehicle with sufficient cross-country

mobility to accompany tanks into action, and with enough armor and firepower to

allow the crew to fight from it, if necessary. Such a vehicle had to meet two

external requirements. It had to be cheap, and it could not interfere with tank

production. That ruled out prima facie any kind of full-track design. Trucks

were disqualified because any reasonably armored version would be heavy enough

to overload suspensions and to lack off-road capacity. The answer came from the

artillery—and indirectly from France.

Even before World War I, truck companies on both sides of

the Atlantic had been experimenting with replacing rear wheels with some sort

of track in order to lessen ground pressure and improve mobility in mud, snow,

and sand. Most prominent in this effort was French engineer Adolphe Kegresse,

whose successful conversion of some of Russian Tsar Nicholas’s autos inspired

the Putilov armaments works to consider a project for military half-tracks.

After the war the French firm of Citroën developed several civilian versions,

staging well-publicized desert crossings in North Africa and central Asia and

attracting the particular attention of a French army still engaged in Morocco

and southern Algeria.

From the later 1920s, half-tracks made up a steadily

increasing percentage of France’s military motor vehicles. Initially and

primarily used as artillery and engineer vehicles, they found their way to the

mounted troops as well. The French cavalry division as reorganized in 1932 had

150 armored versions as reconnaissance and combat vehicles. Another hundred,

unarmored, carried the men and weapons of the battalion of Dragons portés

(motorized dragoons) newly created for each mounted division.

With such an example so ready at hand, as early as 1926 the

Reichswehr’s Weapons Office began preparing its own design for half-track

tractors. Daimler-Benz began working on a production version in 1931; by 1936,

a series of vehicles from one ton to eighteen tons were on the drawing boards

or in the field, mostly as artillery tractors. That reflected, in passing, the

artillerís continued reluctance to accept the urging of the Lutz/Guderian

school and fully mechanize the panzer divisions’ fire support by developing

self-propelled mounts. This was more than commitment to branch self-interest

and a tradition of towing guns into battle. Tracked vehicles were still fragile

relative to the weight and the recoil of even a light field piece like the

standard 105mm howitzer. In addition to probable effects on accuracy, a

breakdown took the gun out of action as well. Not until well into the Cold War

would even the US army abandon towed guns as standard divisional-level weapons.

On the bright side from the panzers’ perspective, Hanomag’s

three-ton tractor seemed well suited to carry a rifle squad. The armored

chassis was provided by Büssing and the fit, if not perfect, was close enough

for government work. At eight tons, with between 8 and 15mm of armor and mounts

for two light machine guns, the 251 was tough and durable, eventually serving

as the mount for a bewildering variety of weaponry. Tracks extending to nearly

three-fourths of the chassis, plus a sophisticated steering system, compensated

for an unpowered front axle and gave the vehicle better cross-country abilities

than its US counterpart and eventual rival.

The technical hair in the soup of the 251 was its

complexity. It may be argued as well that neither the infantry nor the panzers

sufficiently internalized the need to emphasize rapid, large-scale production.

The first A-model versions did not begin service trials until 1939, and there

would never be enough of them to equip more than one battalion in all but a few

favored panzer divisions.

Production delays bedeviled as well the 251’s smaller

cousin. The SdKfz 250 developed out of a growing mid-1930s belief that

reconnaissance was too vital an element of mobile war to be trusted to existing

combinations of motorcycles and armored cars. At times it might be necessary to

fight for information; at times it might be necessary to traverse rough ground

to secure information. The solution was a half-sized half-track built on the

chassis of the 1-ton artillery tractor. At 5.4 tons, with up to 14.5mm of

armor, an open top, and a six-man crew, the 250 could move at almost 40 miles

per hour, cover 300 miles on a single fueling, and, when necessary, put a few

boots on the ground to search, destroy, and provide fire cover. It would not

see service until 1940, but eventually it would prove almost as versatile a

weapons platform as the 251.

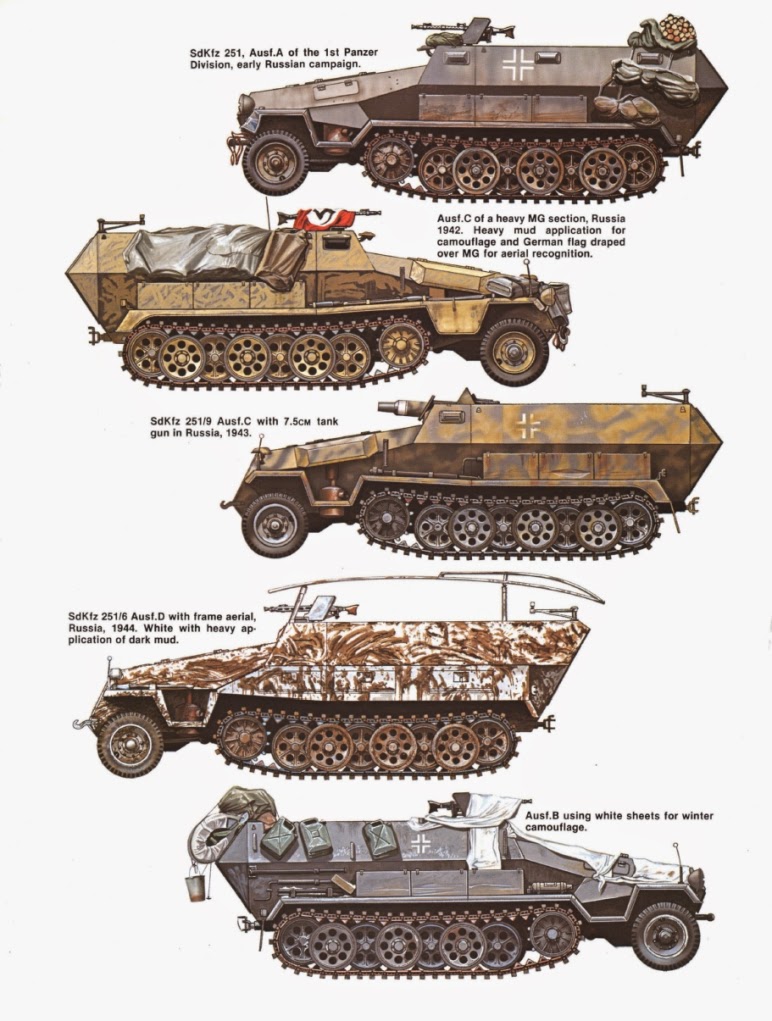

There were four main model modifications (Ausführung A

through D), which formed the basis for at least 22 variants. The initial idea

was for a vehicle that could be used to transport a single squad of

panzergrenadiers to the battlefield protected from enemy small arms fire, and

with some protection from artillery fire. In addition, the standard mounting of

at least one MG 34 or MG 42 machine gun allowed the vehicle to provide support

by fire for the infantry squad once they had disembarked in battle.

Positive aspects of the open top included greater

situational awareness and faster egress by the infantry, as well as the ability

to throw grenades and fire over the top of the fighting compartment as

necessary while remaining under good horizontal cover. The downside was a major

vulnerability to all types of plunging fire; this included indirect fire from

mortars and field artillery, as well as depressed-trajectory small arms fire

from higher elevated positions, lobbed hand grenades, even Molotov's cocktails,

and strafing by enemy aircraft.

The first two models were produced in small numbers from

1939. A and B models can be identified by the structure of the nose armor,

which comprised two trapezoidal armor panels - the lower of which had a cooling

hatch. The B model, which began production in 1940, eliminated the fighting

compartment's side vision slits. The C model, which started production in

mid-1940, featured a simplified hexagonal-shaped forward armored plate for the

engine. Models A through C had rear doors that bulged out. The C model had a

large production run, but was quite complex to build, involving many angled

plates that gave reasonable protection from small arms fire. From early 1943,

the D model was developed with the purpose of halving the number of angled body

plates, simplifying the design and thus speeding up the production. D models

can be easily recognized by their single piece sloping rear (with flat doors).

The standard personnel carrier version was equipped with a

7.92 mm MG 34 or MG 42 machine gun mounted at the front of the open

compartment, above and behind the driver. A second machine gun could be mounted

at the rear on an anti-aircraft mount.

When comparing the M3 with the German Sdkfz.251 halftrack,

you will find both of similar size, speed and weight, but the M3 had over 20%

more internal capacity due to its boxy hull shape. The 251 halftrack was more

thickly armored, and the armor was angled to derive the best protection

possible. But, due to the greater horsepower from the US vehicle's engine, and

the powered front axle, the M3 was a greatly superior vehicle for cross-country

travel. Unfortunately, both vehicles were lacking in over-head protection, a

problem that plagued occupants throughout WWII.

LINK

Hey Mitch - I am a screenwriter doing research on a film project, and i was wondering if you could tell me which book I can buy that has all those nice color illustrations of all the different variations of SDKFZ German half track. (its ones at the top of the page here) Many thanks, Howard McCain

ReplyDelete